Less than a month after the general election held on December 11, a new government formally took office in Romania. As anticipated, a two-party coalition was formed between the Social Democratic Party (PSD), represented by 221 MPs in the 465-seats bicameral parliament, and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), which holds 29 seats. The Hungarian minority party (UDMR), which won 30 seats in the election, signed a parliamentary support agreement with the ruling coalition but decided to stay out of government. Counting in the support of the 17 representatives of the national minorities, the government majority is only 13 seats shy of the two-thirds majority required for a constitutional amendment. The two ruling parties also seized the top legislative posts: PSD’s chairman Liviu Dragnea claimed the leadership of the Chamber of Deputies, while the Senate presidency went to the ALDE leader and former prime minister Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu.

While little time was spent on PSD-ALDE coalition negotiations, President Iohannis’ involvement in government formation delayed the appointment of a new prime minister and came close to triggering a new constitutional crisis. The Constitution grants the head of state some discretion in identifying a prime minister candidate, but the final decision on the approval of a new government rests with the parliament. The president’s actual influence on who gets the PM post depends on political context and is usually limited to situations when either a presidential majority exists in parliament or a deep political crisis opens a window of opportunity for the head of state to put together a “crisis-solving” government. The latter scenario took place in November 2015, when President Iohannis appointed a technocratic government led by former European Commissioner for Agriculture Dacian Cioloş after the then PSD government led by PM Ponta stepped down amid country-wide anti-corruption protests. As the National Liberal Party (PNL) together with the other centre-right groupings barely control 36% of the parliamentary seats in the current legislature, the head of state seemed to have hardly any leeway in the exercise of his PM appointment powers. However, President Iohannis found a way to hinder PSD’s efforts to dictate the formation of the post-election government.

First, he used a 2001 law that forbids convicted persons to be appointed to government as a legal ground to bar PSD’s leader Liviu Dragnea from becoming prime minister on account of a two-year probation sentence for electoral fraud he received in 2015. Dragnea admitted he was unable to claim the PM post for himself “for the time being”, but made it clear he had a free hand from the party to make appointments to cabinet and hold the executive accountable for its actions. Consequently, his first nomination for the PM post was Sevil Shhaideh, a PSD member without a personal power base in the party but one of his longstanding collaborators and loyal supporters. President Iohannis rejected Shhaideh’s nomination without formally motivating his decision. Her Syrian husband’s ties with President Bashar al-Assad’s regime was however seen as the main reason for the president’s unprecedented move to turn down a PM nomination. The PSD-ALDE coalition reacted with threats to initiate the proceedings for the president’s impeachment. This episode ended with President Iohannis’ acceptance of the Social Democrats’ second proposal for prime minister. Sorin Grindeanu, a relatively unfamiliar figure for the general public despite having been a minister in the PSD government ousted in November 2015, presented his cabinet and won the parliament’s investiture vote held on January 4 with 295 votes against 133.

PM Grindeanu’s cabinet profile: “politics is made elsewhere”

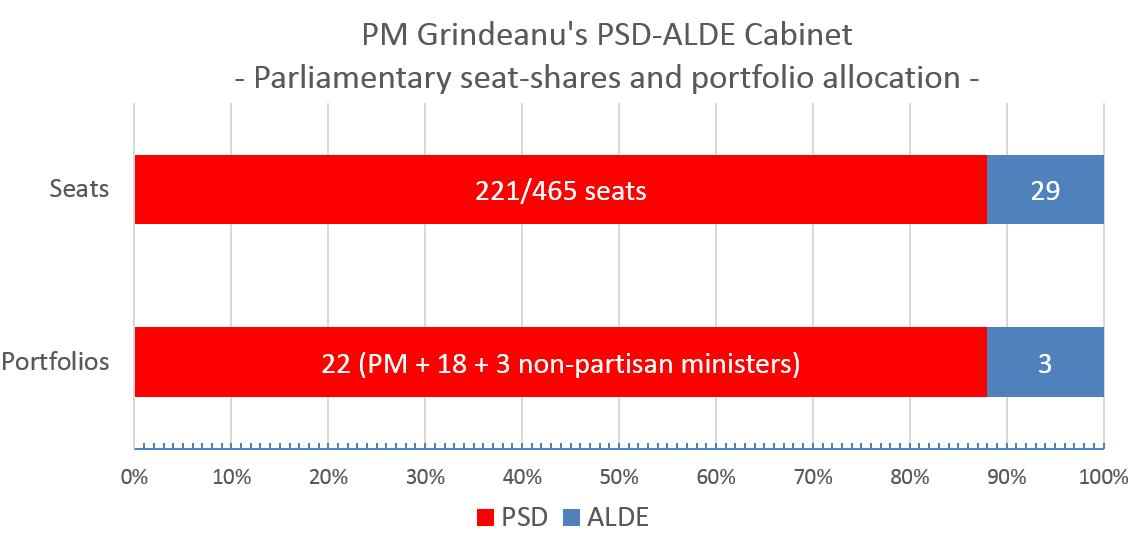

Ministerial portfolios in PM Grindeanu’s cabinet are distributed among the two parties in strict proportion with their legislative seat-shares.

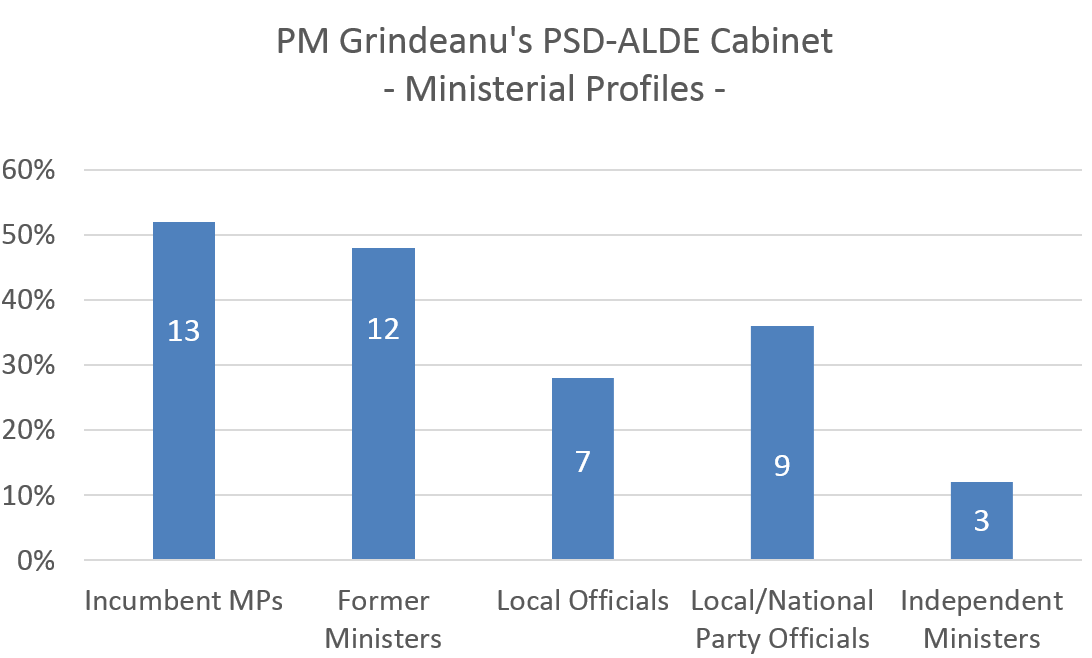

While most members in PM Grindeanu’s cabinet have some experience in national or local politics, few of them are high-profile politicians. About half of the ministers, including PM Grindeanu and deputy PM Sevil Shhaideh, have held posts in previous PSD cabinets. They occupy more or less the same portfolios they held before, despite having left few notable traces in their respective domains. Some of them come from local public administration (Sorin Grindeanu and Sevil Shhaideh fit this profile as well). Only half of the ministers were selected from among the sitting parliamentarians and not many of them have been key figures in their party’s national or local organizations. Moreover, despite PSD’s heavy criticism of the previous government’s technocratic nature, three of the cabinet members have no formal political affiliation. Additionally, several ministers are involved in corruption investigations or other controversies. As a matter of fact, PSD’s governing programme does not contain any references to continuing the fight against corruption.

Arguably, the ministers’ lack of personal notoriety makes them more susceptible to direct party control. The prime minister himself is better known as a local politician, due to his recent election as president of the Timiş City Council, despite having been a deputy in the 2012-2016 legislature and a minister in PM Ponta’s last cabinet. Although a longstanding PSD member, Sorin Grindeanu has never held a key position in the party’s national executive. That said, it is not unprecedented for a prime minister not to be a party leader as well. For example, PM Ponta stepped down as PSD leader in July 2015, after prosecutors from the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA) opened a corruption investigation against him (ironically, he was succeeded as party leader by Liviu Dragnea, who had already received a one-year suspended jail sentence for electoral fraud). Even in the French Fifth Republic, where control over the party machinery is often thought a prerequisite for the exercise of key executive roles, Lionel Jospin willingly resigned as leader of the Socialist Party before taking office as prime minister in 1997 (also at the beginning of cohabitation with President Chirac). In these cases, though, the prime ministers’ political authority over their governments’ actions and even on their parties was not questioned. This is hardly the case with PM Grindeanu, who lacks a personal power base in the party. In fact, one might be hard pressed to find another example of a prime minister stating that his cabinet has a purely administrative role, as “politics is made elsewhere”.

All important decisions following the general election have been announced by PSD’s leader Liviu Dragnea, including the formal presentation of PM Grindeanu’s list of ministers. In fact, he repeatedly stated that the government is directly accountable on the party line and that he will personally monitor each minister’s performance. Dragnea has also taken over announcements concerning the steps taken by the government to fulfill the generous promises of the Social-Democratic programme, such as the swift elimination of the income tax for small pensions. Thus, as leader of the main governing party and president of the Chamber of Deputies, Liviu Dragnea possesses all essential tools to control and speed up executive actions, acting as the country’s most powerful politician.

President Iohannis’ role in the fourth cohabitation

Although this is Romania’s fourth spell of cohabitation, it is the first time that a general election brought it about. There are good chances it will also be Romania’s longest cohabitation to date, as the next presidential election is not due before late 2019. Therefore, one can only speculate about the role President Iohannis will choose to play from now on, especially if he intends to run for a second mandate. Granted, it is too early to tell if he will attempt to redefine his role as the leader of the opposition, like his predecessor did in 2007 and 2012. However, there are signs he might be willing to take a more active role in the confrontation with the ruling coalition.

For example, the head of state delivered a tough speech at the government’s swearing-in ceremony on January 4. On this occasion, he picked holes in the governing programme for not specifying how it will manage to keep the budgetary deficit under 3%, while making populist promises to increase salaries and pensions and cut down the VAT. He also hinted at the ministers’ inability to answer basic questions related to the governing programme during the parliamentary hearings, which were cut down to only 30 minutes for each minister.

Notable among the president’s latest actions were also his blasting comments on the Ombudsman’s decision to challenge the law banning convicted persons to join the government to the Constitutional Court. In fact, the Ombudsman’s action is generally seen as a blatant attempt to ease Liviu Dragnea’s future accession to the prime ministership. The president made similar harsh remarks several days later, when he warned the government against attempting to pass a law on amnesty and pardon of convicted or prosecuted politicians. He also pledged support to the DNA’s internationally recognised anti-corruption fight and vowed to use his veto powers against legislative and executive actions directed towards the weakening of anti-corruption legislation.

Whether such pledges can still pay off electorally – a view the latest polls did not seem to support – or have any political effects in the face of PSD’ solid parliamentary majority remains to be seen. For the time being, the PSD-ALDE majority has just engineered the government’s ability to govern through emergency ordinances that do not require the president’s approval while the parliament has convened for an extraordinary session.