One year after country-wide anti-corruption protests forced Victor Ponta’s Social-Democratic government out of office, the PSD won a landslide victory in the general election held on December 11. The Social-Democrats have topped the polls in each general election held since 1990 and formed the government each time a centre-right coalition was too weak or too divided to coalesce around a common leader. This time, though, their historic 46% of the vote might bring along an outright parliamentary majority – a first in Romania’s post-communist electoral history – after the redistribution of unallocated mandates. However, despite the clear election results, a political crisis might still be looming on the horizon. During the electoral campaign, President Iohannis vowed not to nominate a convicted politician as prime minister, a situation which includes the PSD leader, Liviu Dragnea, who received a two-year probation sentence for electoral fraud earlier this year.

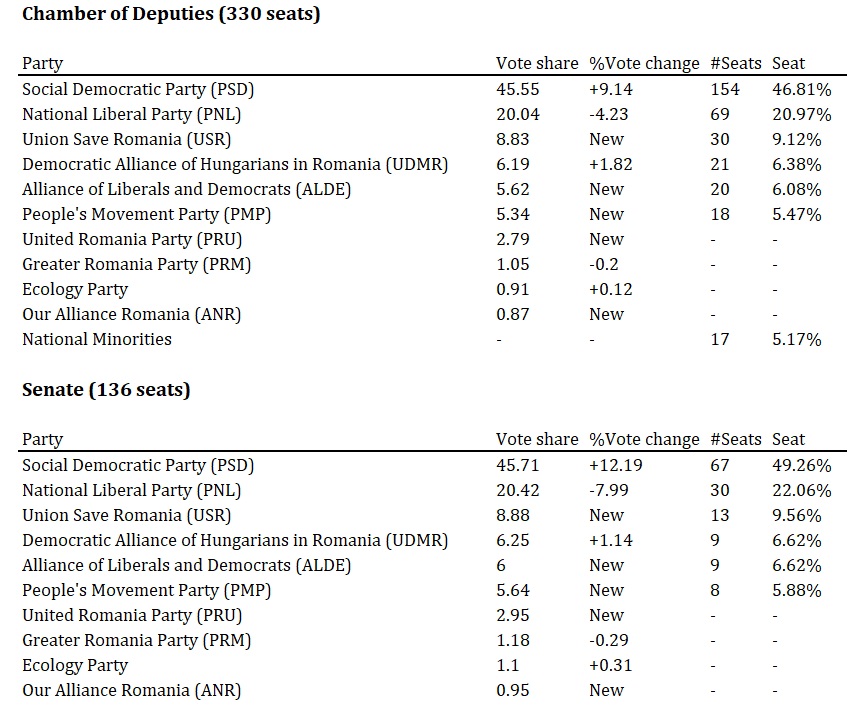

Election results

The Social-Democrats are followed by President Iohannis’ National Liberal Party (PNL) with a distant 20%. Since the local elections held in June, the party has lost about 10% of the voters’ preferences. The election outcome is all the more disappointing for the PNL, as one year ago the party could count on 35% of the public support according to opinion polls. However, instead of calling early election when the PSD government was ousted, President Iohannis chose to appoint a technocratic government led by former commissioner Dacian Cioloş. Some of the PNL’s eroding support was captured by the Save Romania Union (USR), a new anti-corruption party set up only six months ago, which won around 9% of the vote.

Apart from the Hungarian minority party (UDMR), two new parties also managed to cross the 5% national threshold: the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), which is the merger between a PNL faction and the Conservative Party (PC) led by former prime minister Călin Popescu Tăriceanu; and former President Băsescu’s Popular Movement Party (PMP), which broke away from the Liberal Democratic Party (PDL) in 2013 (the other PDL faction merged with PNL in 2014 and supported Klaus Iohannis as a common candidate in the 2014 presidential election).

None of the 44 independent candidates who stood for election across the country’s 42 constituencies managed to obtain an electoral mandate. A couple of newly-formed ethno-nationalist parties also run unsuccessfully, proving that xenophobia and far-right extremism have not found fertile ground in Romania. That said, the election winners were able to capitalise on growing anti-EU sentiments. Turnout to vote was just 39.5%, the lowest on record since 1990. The full allocation of seats in the two parliamentary chambers is yet to be determined.

Figure 1. 2016 General Election Results

The electoral campaign

Several factors contributed to the PSD’s stunning victory. The new electoral legislation, as well as the laws on political parties and campaign financing adopted by the parliament in 2015 played a significant role. A previous post discussed the change in electoral rules, from the mixed-member system used in the 2008 and 2012 elections to the closed-list proportional system with moderately low-magnitude districts, which was employed until 2004. The new law on party financing capped campaign budgets for individual candidates to 60 gross average salaries, severely restricted the range of electioneering activities – such as street advertising and the dissemination of electoral gifts – and increased the parties’ dependence on state budget for campaign spending. These regulations favoured the two big parties, the PSD and the PNL, and limited the ability of newer parties to make themselves known outside the big cities. Under these circumstances, door-to-door canvassing and online campaigning became an essential part of campaign strategies. These techniques were also skilfully used by USR, due to its strong ties with civil society and its popularity among educated voters who are more likely to use the internet for political information.

The depersonalisation of the electoral campaign was another factor that enhanced the Social-Democrats’ chances (or at least prevented them from haemorrhaging support as in 2014, when the centre-right electorate mobilised against Victor Ponta and handed over the presidency to Klaus Iohannis). The campaign lacked the usual debates between party leaders and PM candidates and the clash of political programmes and policy proposals. Learning the lesson of the 2014 presidential election, the PSD refrained from making any nominations for prime minister, although everything pointed to its current leader, Liviu Dragnea, as the party’s first choice for the PM post. As Dragnea received a two-year probation sentence for electoral fraud earlier this year, his endorsement for the prime ministership ahead of the election would have been an easy target for the centre-right parties, which campaigned on an anti-corruption platform.

On their side, PNL and USR chose to associate themselves with the record of the technocratic government, praising its efficiency in the reform of central and local public administration. Both parties tried to lure PM Cioloş into their ranks. When the premier turned down their offer, the two parties ended up endorsing his political platform and nominating him for a second term as head of government. The move backfired for two reasons. On the one hand, it showed that PNL is still in search of leaders for top national positions, a weakness that also cost the party the defeat in the race for the mayor of Bucharest in the June contest. In fact, PM Cioloş was reluctant to even take part actively in the campaign. On the other hand, it allowed the PSD to associate the centre-right parties with the mishaps of the Cioloş government and its refusal to consent to populist public spending measures passed by the PSD parliamentarians in the eve of the electoral campaign. Moreover, just a few days before the general election, PSD presented plans for next year’s budget , which included proposals for a national reindustrialisation programme and consistent wage increases for public sector employees. This generous stance on boosting social spending and tax cuts was contrasted with PM Cioloş’ firm position on containing the budget deficit, despite Romania’s GDP growth by 6% this year.

Although President Iohannis refrained from getting too involved in the campaign, he did make three notable interventions. First, he tried to force PM Cioloş into joining the PNL ranks by announcing that he would not appoint an independent prime minister after the December poll. Faced with the premier’s refusal to join a political party, the president backed down saying that Cioloş could in fact continue in office if political parties endorsed him for a second mandate. The second time President Iohannis showed off his constitutional role in PM appointment, he ruled out designating a criminally prosecuted or convicted politician, regardless of that person’s parliamentary support. Then, less than a fortnight before the election, he prohibited officials with a criminal record to take party in the formal celebrations organised for Romania’s National Day on December 1. As a result, several high-ranking PSD and ALDE politicians, including Liviu Dragnea and former PM Popescu-Tăriceanu, were denied access to high-visibility events organised by the Presidency. Arguably, these interventions anticipated the President’s intention to make active use of his formal powers in government formation and to prevent the PSD leader from taking over as prime minister.

Towards a new government and another period of cohabitation

Although the allocation of seats has not been officially announced yet, the Social-Democrats and their smaller ally ALDE are likely to reach a sizeable majority. Consequently, the PSD will be granted the first chance in nominating a new prime minister candidate. While so far no official proposals have been made, senior PSD figures have strongly endorsed their party leader for this role. However, not only has President Iohannis vowed to deny appointment to convicted politicians, but a 2001 law also forbids convicted persons to be appointed to government posts. Nevertheless, PSD insists that constitutional provisions, according to which the president must appoint a candidate for the PM post following consultations with the party holding the absolute majority in Parliament, should take precedence in this case. As Liviu Dragnea is unlikely to allow a political rival to capitalise on his electoral success, the conditions for a new constitutional crisis seem in place. Its resolution might once again depend on the decision of the Constitutional Court, or, as several PSD members suggested, could lead to another attempt to impeach the president.

Either way, Romania seems headed towards a new period of cohabitation. It will be interesting to see what role President Iohannis will choose to play in this situation. Will he attempt to become the leader of the opposition, like Traian Băsescu in 2007 and 2012? So far there have been few signs of the president’s willingness to take an active role in the confrontation with political parties. That said, the presidential elections scheduled for 2017 could provide a strong enough incentive to capitalise on the eventual eroding popularity of the centre-left government.